Suffering from "shell shock and a general breakdown," Charles Mackall and James Randall arrived in Philadelphia in September 1918 from military service in France in the Great War. Mackall had been in trenches on the front line and had lain unconscious for 10 days. Randall had been a water tank driver. His afflictions, a newspaper article in The Chicago Defender reported, had left him unfit for military service.

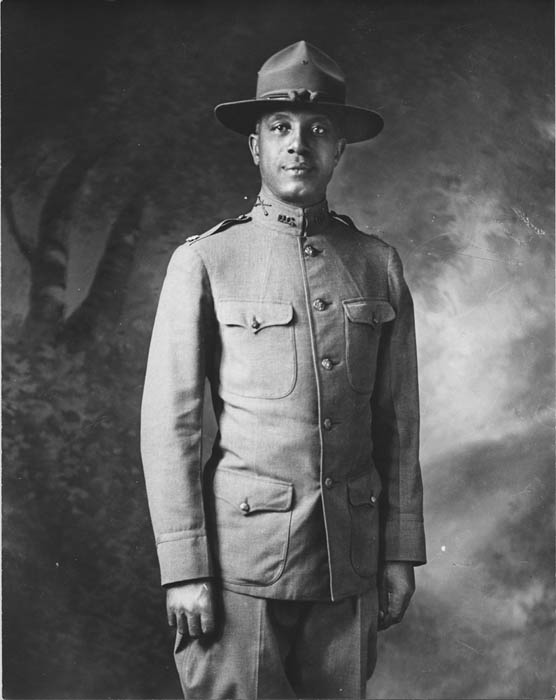

The men belonged to the United States Army's 301st Quartermaster Corps, a unit providing support to combat troops. In spite of their service to the country and their "invalided condition," the two injured soldiers lacked access to medical care available to other troops. The reason: Mackall and Randall were African American. However, thanks to the philanthropic efforts of black Americans and white supporters, both men "were immediately provided for," the Defender explained, "by the Crispus Attucks Circle, an organization for war and relief work among our Race."

Since the colonial era, in times of peace and war, the African American experience of inequality included being denied medical treatment equal to that received by white peers. Unequal treatment continued during World War I. Not even the era's increasing humanitarian efforts were immune to inequality.

After the United States entered the conflict in April 1917, millions of Americans donated to the American Red Cross and other relief agencies to help U.S. troops and foreign civilians. Along with their other contributions, women knitted hats, mittens, and other woolens for soldiers; conserved foodstuffs to ensure an adequate supply for the military and overseas civilians; and volunteered at recreational centers for troops stationed in the United States. Thousands of women volunteered to go abroad to aid soldiers and foreign civilians. These and other contributions made by millions of Americans provided vital aid to American troops and extended the tradition of American philanthropy overseas to assist many more people. African American women and men participated in the ways all Americans did, yet white-led relief organizations routinely maintained segregated facilities, limited opportunities for black community members to become involved, and denied or provided unequal services to black soldiers and civilians.

In the face of this long history of discrimination, African Americans during World War I worked to help members of their community. The Crispus Attucks Circle for War Relief, the group that helped Mackall and Randall, was one such effort. Led by the well-known Archdeacon Henry L. Philips and other African American community leaders, the organization raised funds for Mercy Hospital, a new hospital being built under African American control to serve African American soldiers.

The group's name honored a notable figure from the country's founding years. In 1770 Crispus Attucks, a Massachusetts man of African and Native ancestry, was the first casualty of the Boston Massacre and thus of the American Revolution. Invoking Attucks reminded the public of the sacrifices African Americans had long made for the country.

The aims of Mercy Hospital encompassed more than providing medical care to African American patients. The hospital also sought to employ and train black medical staff. That aspect of the mission helped efforts to promote equality by creating professional opportunities for black doctors and nurses, who were denied similar opportunities in other hospitals. An increase in well-trained African American medical staff promised greater access to good medical care for African American patients.

Mackall and Randall received assistance from the Crispus Attucks Circle while work on Mercy Hospital was underway. By the spring of 1919, the hospital was ready to open formally. Many people contributed—from John T. Gibson, a successful African American theater owner who donated a couple days' proceeds, to John Wanamaker, a white department store magnate whose store featured a window display for the fundraising drive. On June 1, the hospital was dedicated. Various dignitaries spoke, and, as a newspaper reported, "solos were rendered by Mme. Florence Cole Talbert, of Detroit, and Miss Marian Anderson" of Philadelphia.

In 1943, when the United States was fighting in another world war, the now-famous Anderson sang at an American Red Cross benefit held at Constitution Hall. A few years earlier, she had been denied the opportunity to perform there because of her race. At this event, not only did she perform, but also the hall sold tickets "without discrimination." Like many other African Americans, she was again contributing to the country's war and relief efforts. She was also continuing the struggle for African American equality and independence that had shaped the philanthropy of supporters of the Crispus Attucks Circle.

Amanda B. Moniz is the David M. Rubenstein Curator of Philanthropy in the Division of Work and Industry.

The Philanthropy Initiative is made possible by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and David M. Rubenstein, with additional support by the Fidelity Charitable Trustees' Initiative, a grantmaking program of Fidelity Charitable.