Some objects are donated to the museum as singular items, but many donors were collectors, aficionados, or experts in their field who bequeathed their private collections into the public coffers of the Smithsonian upon their passing. Such is the case with the Grant Wheat collection of mining lamps that were donated to the museum by his widow Mary Wheat in 1961. Grant Wheat left a lasting impact on the mining lamp industry thanks to his invention of the rechargeable battery-powered Wheat incandescent lamp in 1918. The lamp received approval from the Bureau of Mines in 1919, and has been manufactured by Koehler Lighting Products of Marlborough, Massachusetts. The Wheat lamp was also licensed by Oldham & Son, a large battery manufacturer in England who used Wheat’s designs to sell their lamps in the United Kingdom and Australia. Koehler has continued to produce Wheat brand lamps into the 20th century.

The Wheat collection illustrates the genesis and development of the rechargeable battery-powered Wheat Lamp during the 1920s and 1930s. The Wheat collection also includes several batteries for hearing aids, as Wheat owned patents relating to the improvement of hearing aid batteries. Puzzlingly, though, Wheat’s donation contained a disparate collection of old lighting artifacts including several torches, pottery lamps, candles, and candle molds that seemed incongruous with the battery-powered lamps in the accession. Reading Grant Wheat’s “Story of Underground Lighting” published in the 53rd Proceedings of the Illinois Mining Institute provided the necessary framework for the collection. The objects were collected to document Wheat’s history of underground lighting, from antiquity to the development of the battery-powered cap lamp, which he presented at the 1945 Annual Meeting of the Illinois Mining Institute.

|

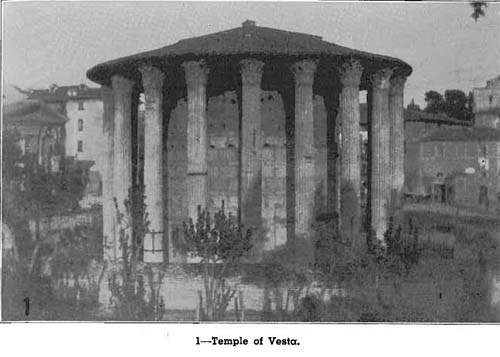

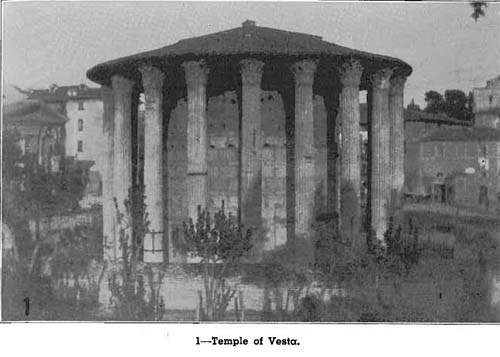

The Roman Temple of Vesta. Click for images from the "Story of Undergroun Lighting."

|

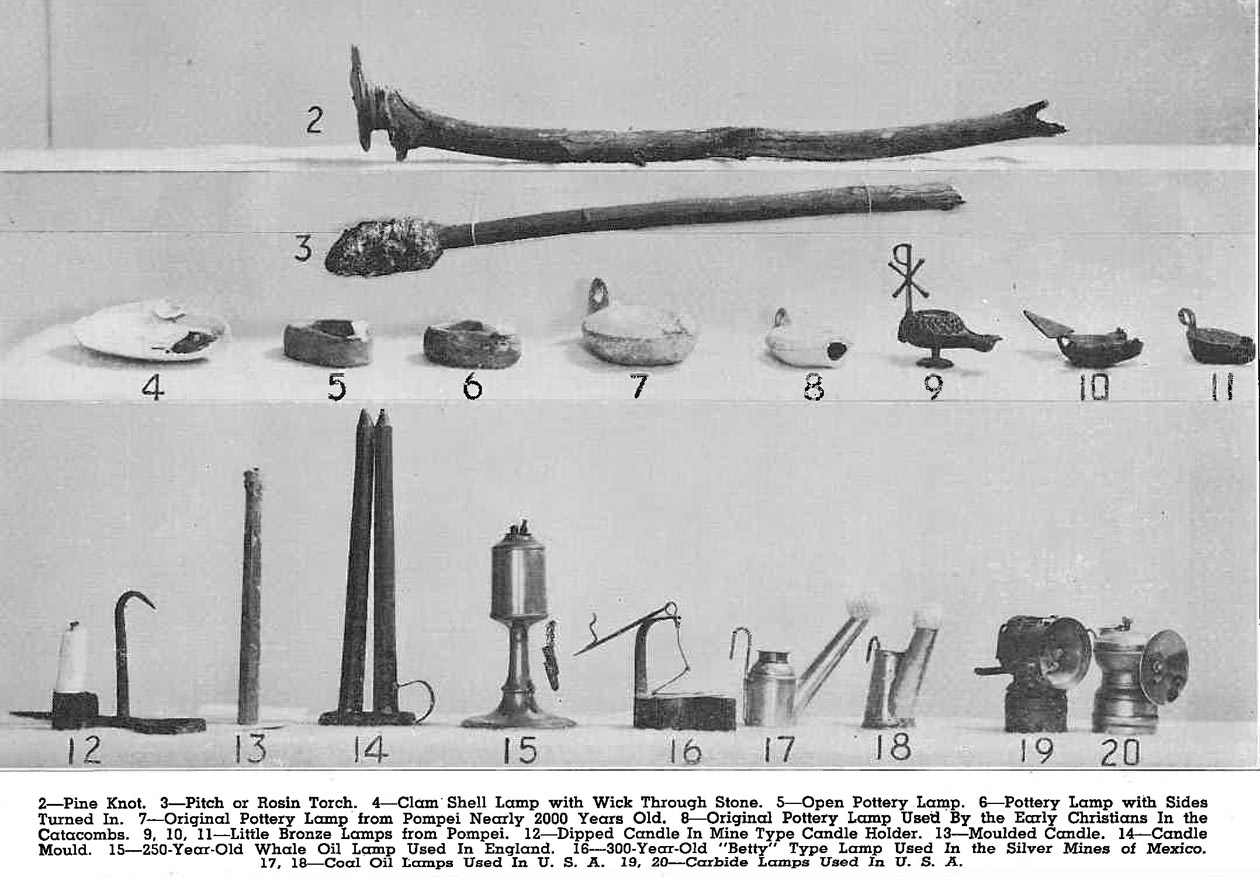

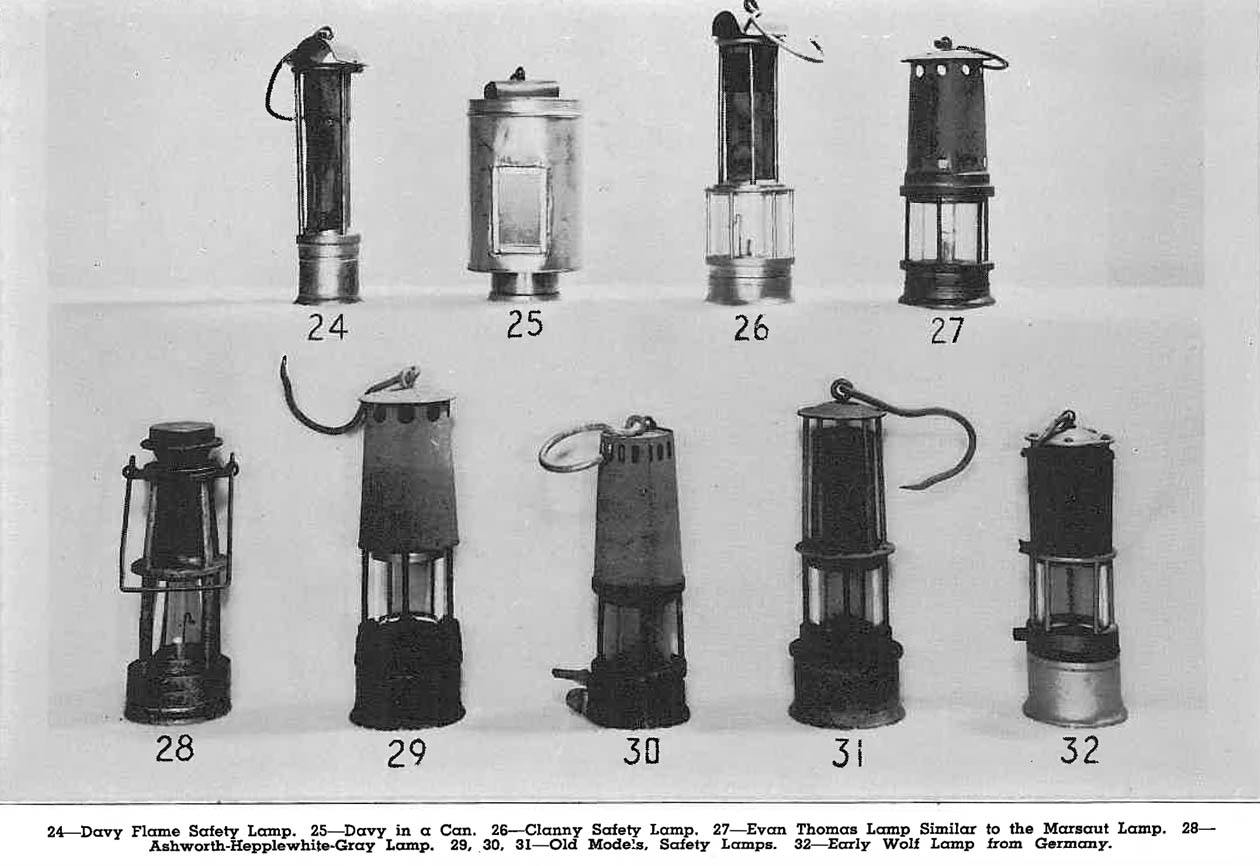

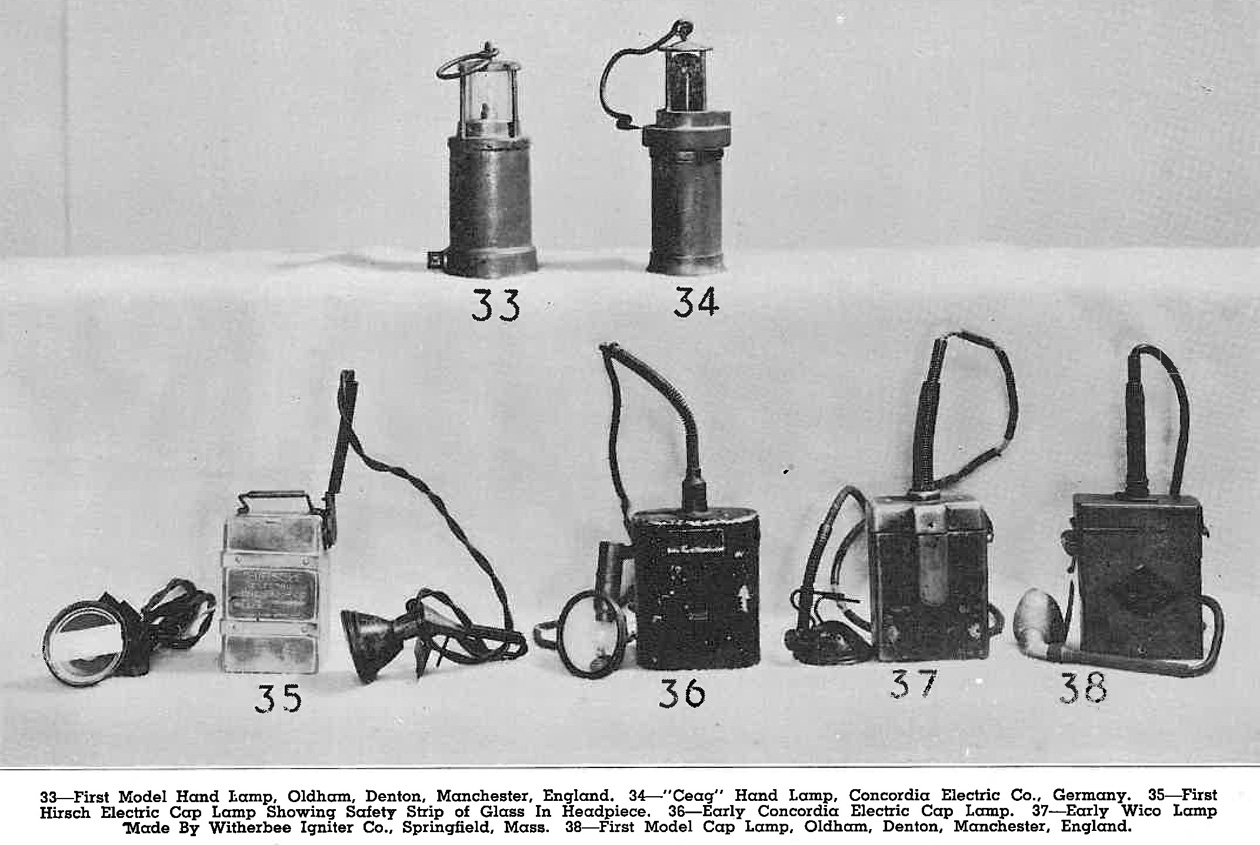

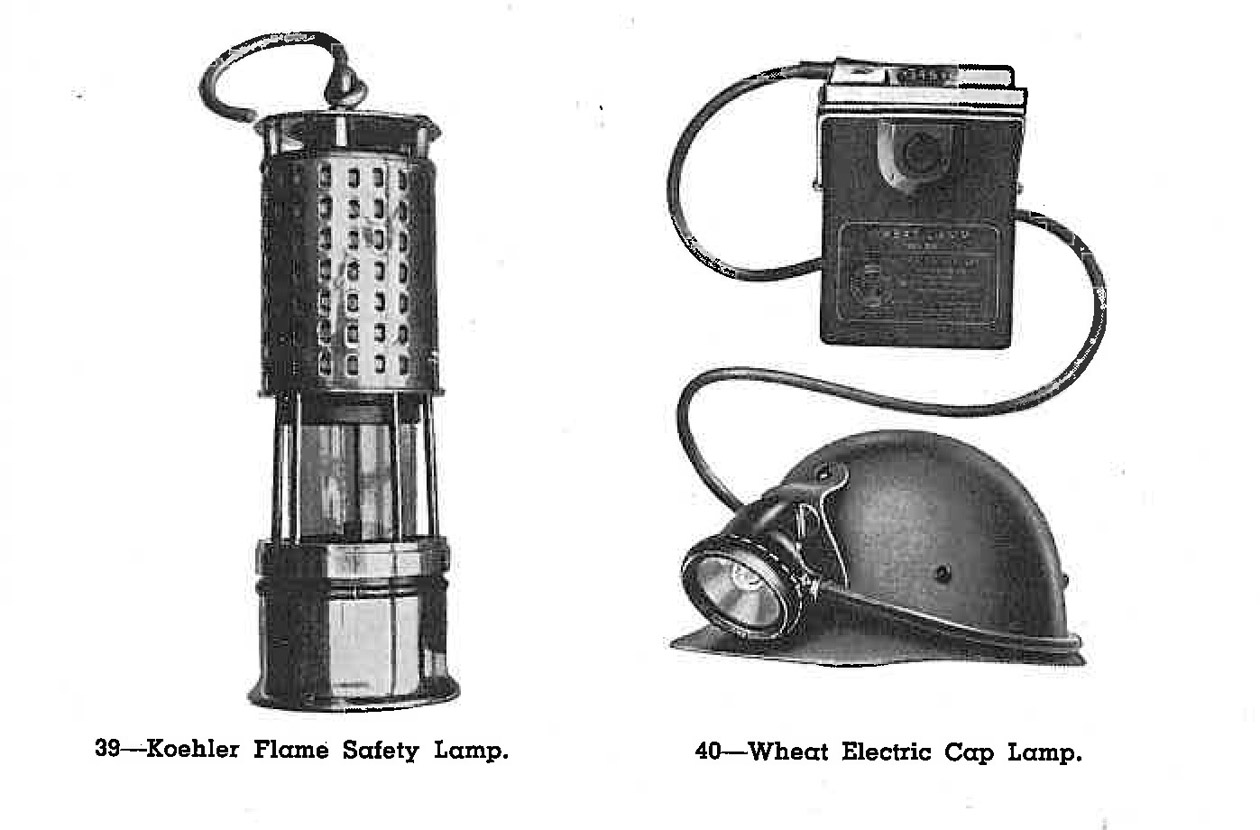

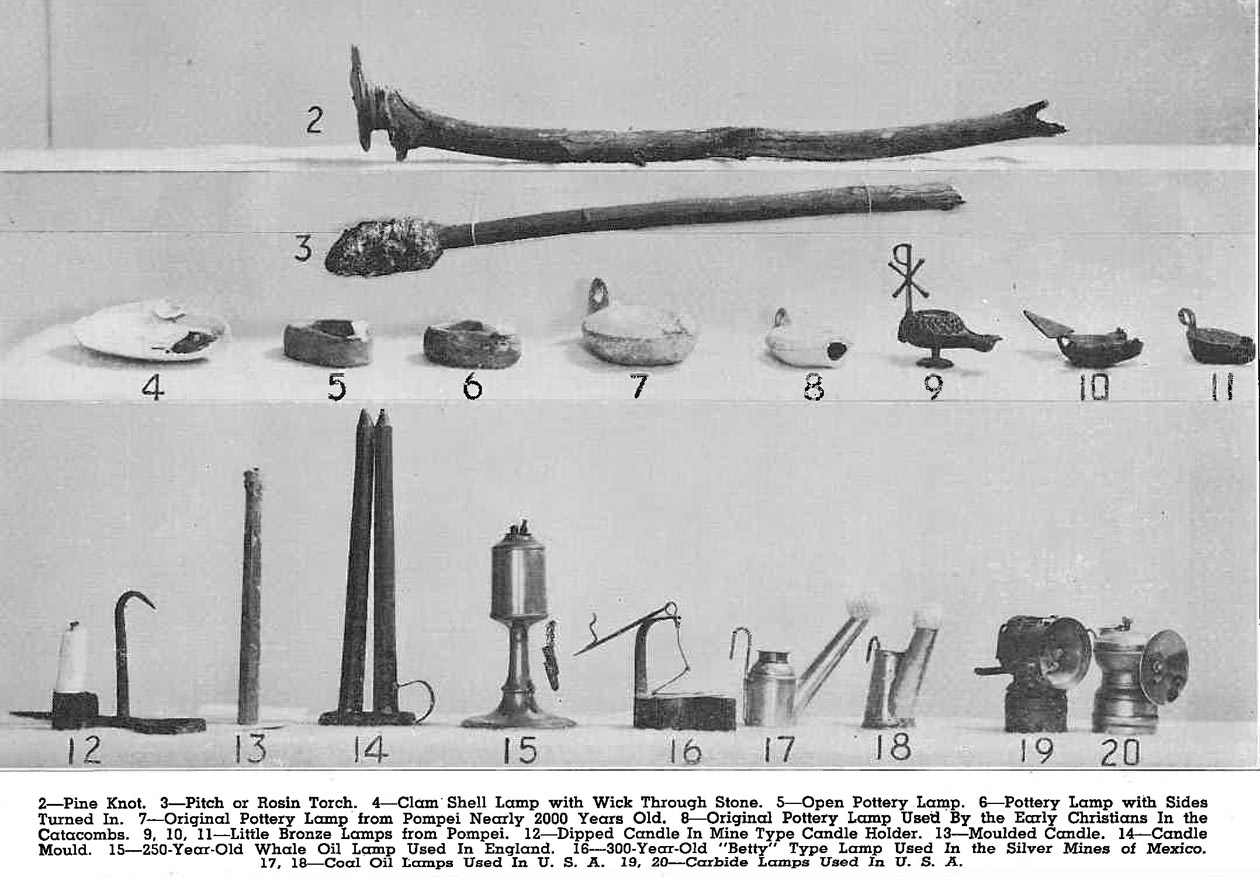

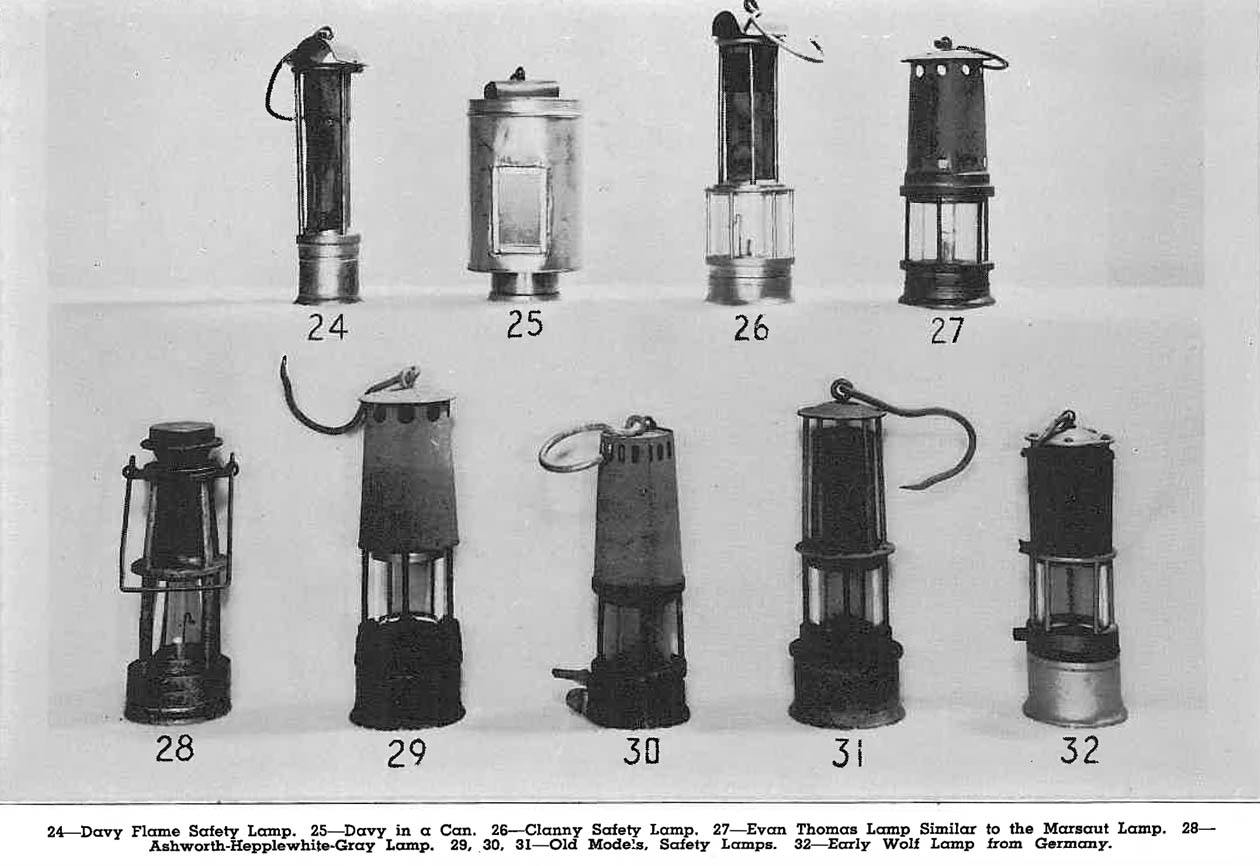

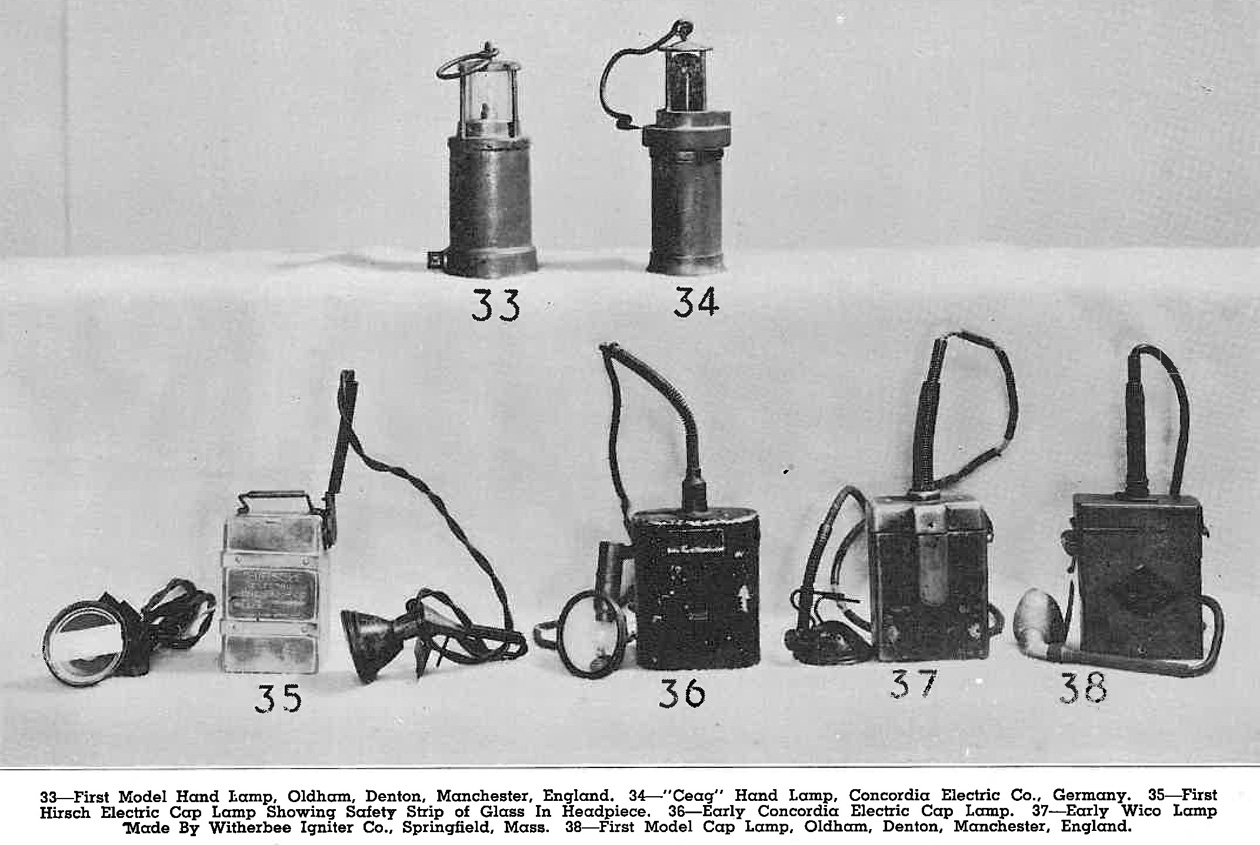

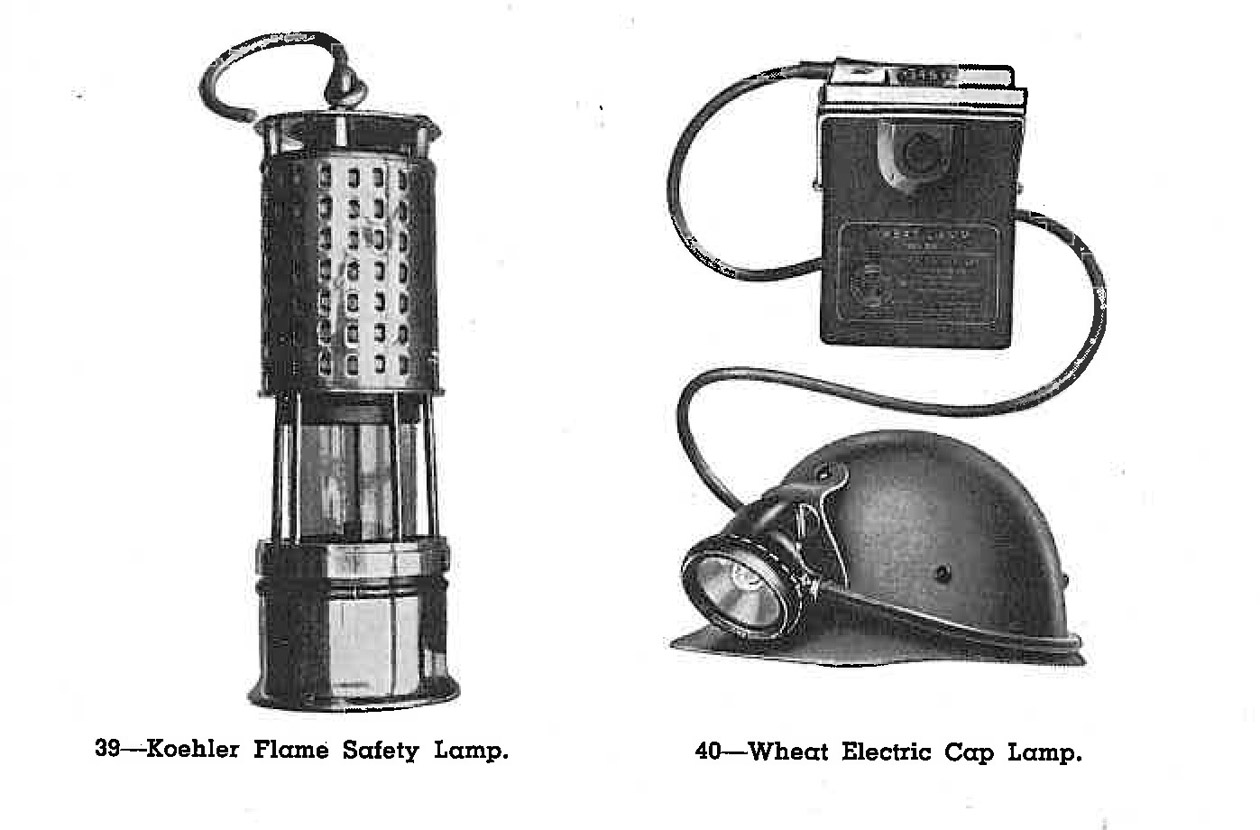

Wheat began his presentation by noting the sacred nature of fire in Rome, where a fire was maintained at the Temple of Vesta. Torches were the next iteration of lighting, followed by pottery lamps. Pottery lamps gave way to candles, which led to metal lamps, which were eventually converted into small metal cap lamps designed expressly for mining. The development of mining lamps continued with carbide lamps, which could still cause methane explosions due to their exposed flame and prompted a need for safer lighting. Safety lamps followed with contemporaneous designs from Sir Humphry Davy, William Clanny, and George Stephenson produced around 1813. During the early 20th century, battery-powered lamps began to replace flame lighting. One of the first battery-powered lamps was the CEAG hand lamp made in England in 1912. In the United States battery-powered cap lamps manufactured by Edison, Hirsch, Concordia, Witherbee, and Koehler were all approved by the U.S. Bureau of Mines from 1915 through 1917. Wheat ends his history of underground lighting with the Koehler Flame Safety Lamp and the Wheat Electric Cap lamp.

Wheat began his presentation by noting the sacred nature of fire in Rome, where a fire was maintained at the Temple of Vesta. Torches were the next iteration of lighting, followed by pottery lamps. Pottery lamps gave way to candles, which led to metal lamps, which were eventually converted into small metal cap lamps designed expressly for mining. The development of mining lamps continued with carbide lamps, which could still cause methane explosions due to their exposed flame and prompted a need for safer lighting. Safety lamps followed with contemporaneous designs from Sir Humphry Davy, William Clanny, and George Stephenson produced around 1813. During the early 20th century, battery-powered lamps began to replace flame lighting. One of the first battery-powered lamps was the CEAG hand lamp made in England in 1912. In the United States battery-powered cap lamps manufactured by Edison, Hirsch, Concordia, Witherbee, and Koehler were all approved by the U.S. Bureau of Mines from 1915 through 1917. Wheat ends his history of underground lighting with the Koehler Flame Safety Lamp and the Wheat Electric Cap lamp.

The objects below are the objects depicted in Grant’s “Story of Underground Lighting” that were donated as part of the Wheat collection. While not definitive or comprehensive, Wheat’s presentation is an interesting overview of the development of lighting from an inventor prominently involved in the history of lighting during the early 20th century. More of Wheat’s battery-powered cap lamps can be seen in the “Electric Lamps” section.