This is a device for introducing elementary school students to the concept of place values. Six parallel wires, each in the shape of an inverted U, fit into holes in a wooden block that serves as a base. Each wire carries nine beads.

- Description

-

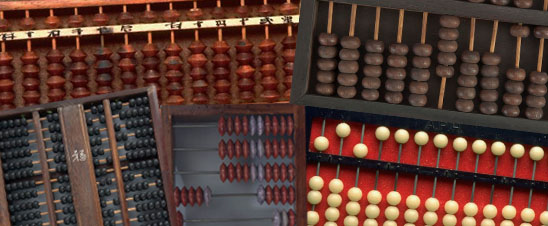

This is a device for introducing elementary school students to the concept of place values. Six parallel wires, each in the shape of an inverted U, fit into holes in a wooden block that serves as a base. Each wire carries nine beads. The beads on the front of the wire represent digits. A tape that runs across the block contains labels for the wires - from one on the rightmost wire to hundreds of thousands on the leftmost. Robert Naidorf (born 1961), the son of the donors, made the object in about 1968. It was used by Marjorie Naidorf, Robert's mother, as a third grade teacher at Parklawn Elementary School from 1971 until 1991. Place value boards are also sold commercially.

- Location

-

Currently not on view

- date made

-

1968

- maker

-

Naidorf, Robert

- ID Number

-

2005.0055.01

- catalog number

-

2005.0055.01

- accession number

-

2005.0055